Letters Of Benjamin Franklin

|

| updated |

Copy Link Code

|

Benjamin Franklin was a popular man even since his days as a young printer in Philadelphia. Many of the famous quotes and sayings he left behind were originally found in his personal letters and only became well known after his time. Many of the letters of Benjamin Franklin were written to his common law wife, Deborah Read Franklin, while he journeyed to Europe and left her to mind their affairs in Philadelphia. Before the death of his parents, who lived in his hometown of Boston, Franklin kept up regular correspondence with them and offered medical advice from his self-educated perspective. As he began to delve into the realm of scientific discovery, Franklin shared his ideas and plans for experiments with scientists in America as well as Europe. His time as a diplomat in London before the Revolution was marked by a series of political letters to Members of Parliament as well as political leaders in the colonies; Franklin maintained a sensitivity for the popular politics of the colonists he was to represent and his letters on the Stamp Act demonstrate an initiation of pro-independence views. In the last decade of his life, Franklin wrote numerous letters explaining his experience and ideas to inquiring minds; these letters, along with his autobiography, provide an excellent image of Franklin for historians to utilize.

Benjamin Franklin was a popular man even since his days as a young printer in Philadelphia. Many of the famous quotes and sayings he left behind were originally found in his personal letters and only became well known after his time. Many of the letters of Benjamin Franklin were written to his common law wife, Deborah Read Franklin, while he journeyed to Europe and left her to mind their affairs in Philadelphia. Before the death of his parents, who lived in his hometown of Boston, Franklin kept up regular correspondence with them and offered medical advice from his self-educated perspective. As he began to delve into the realm of scientific discovery, Franklin shared his ideas and plans for experiments with scientists in America as well as Europe. His time as a diplomat in London before the Revolution was marked by a series of political letters to Members of Parliament as well as political leaders in the colonies; Franklin maintained a sensitivity for the popular politics of the colonists he was to represent and his letters on the Stamp Act demonstrate an initiation of pro-independence views. In the last decade of his life, Franklin wrote numerous letters explaining his experience and ideas to inquiring minds; these letters, along with his autobiography, provide an excellent image of Franklin for historians to utilize.

The earliest Ben Franklin letters to garner attention were actually written anonymously. While he was just a teenager working as an apprentice in his older brother's print shop, Franklin got the idea that he would like to write. His brother, James, had recently established a newspaper called The New England Courant and was open to including essays and opinions from local writers, but not from his younger brother. Despite James' denial, Benjamin devised a way to get published in the paper anyway. He wrote a series of letters under the nom de plume Mrs. Silence Dogood, a name inspired by the teachings of a Puritan preacher, Cotton Mather. Despite the popularity of the Dogood letters, James Franklin was infuriated when Benjamin admitted his deception and their relationship would never heal. This dispute was a catalyst for Benjamin's departure from Boston, first to New York and soon on to Philadelphia.

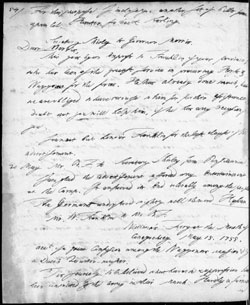

In the time of Benjamin Franklin, letter writing was of course the most relevant means of long distance communication. Franklin himself served as a Postmaster, first for Pennsylvania before his appointment to be Joint Deputy Postmaster-General of North America beginning in 1753. With his invention of the odometer, Franklin was able to bring much greater efficiency to the mail service and even increased the frequency of delivery to once a week instead of twice a month. Franklin only lost this position after leaking another man's sensitive letters, but only for patriotic purposes. In 1774, Franklin discovered letters from the Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, requesting more British troops to squash the rebellious population. After they were leaked to the Sons of Liberty, John Adams brought them into the public light. Franklin admitted his culpability in the scandal only after three innocent men were implicated. He was ridiculed before Parliament and sent back to Philadelphia where he would help to write the Declaration of Independence only two years later.